Viscous Apocalypse: László Krasznahorkai’s Weird Literary Worldbuilding

László Krasznahorkai. Image sourced from Flavorwire.

Like many other readers in the English-speaking world, I first came to László Krasznahorkai through the films of his fellow Hungarian, Béla Tarr. My own roundabout path from Tarr back to Krasznahorkai took more than a decade, and in retrospect I feel certain that this detour proved crucial to my eventual appreciation of Krasznahorkai’s work. You might say that Tarr’s films implanted in me a particular fascination that Krasznahorkai’s fiction would not just echo, but amplify. Without Tarr, Krasznahorkai might never have (re)entered my consciousness, and almost certainly not at the time he did, just as I was embarking on new project on the mysterious relationship between worldbuilding and apocalypse in contemporary literature. Anyone who has read Krasznahorkai will, I think, immediately understand his relevance to such a project. One need only peruse the covers of his novels, most of which have emblazoned on them Susan Sontag’s claim that Krasznahorkai is the “contemporary master of the Apocalypse.” But there is a particular quality that intrigues me about Krasznahorkai’s apocalyptic vision, a curious philosophical and literary density. It is this density—or perhaps it will be better to call it “viscosity”—that I wish to explore here. And since, as I’ve suggested, my sense of this viscosity has been conditioned by Tarr’s extraordinary cinematic work, allow me to begin there.

∞ ∞ ∞

I don’t actually remember how I first learned Béla Tarr’s name, or what brought about my first encounter with his late-career masterpiece, Werckmeister Harmonies (2000). In spite of this haze, however, the memory of my first viewing remains indelible. The first thing I recall is the somewhat grainy nature of the black-and-white cinematography. The granularity of the picture struck me, because it reminded me of another somber film I’d recently seen: E. Elias Merhige’s Begotten (1990), an almost unwatchable, grainy film that opens with a strange scene where a robed figure – “God” – ritually disembowels himself. (Incidentally, Begotten happened to be another cult favorite of Susan Sontag, who reportedly deemed it “one of the 10 most important films of modern times.”)

With this initial comparison in mind, I grew worried that I had strayed into another confounding experimental film that would by turns baffle and bore. My concern increased as the opening scene drew on. The scene, which featured a sober young man named János in a bar full of drunk older men, progressed very slowly. It appears to be nearly closing time as János addresses the others. He recites a poem about a total solar eclipse, and he directs the men to interpret the poem as a dance. The men coalesce into a teetering model of the solar system, with each person symbolizing a planet or satellite, one spinning around another spinning around another. Between the poem and the dance, the whole scene feels pointedly meaningful, with order swirling swiftly into chaos. With the overwrought symbolism of Begotten still echoing in my head, I couldn’t help but wonder what might be in store for me here.

But Werckmeister quickly proved to offer a rather different cinematic experience than my initial comparisons to Begotten suggested it might. What alerted me to this difference was the recognition, about 8 minutes in, that the entire opening scene had unfolded in a single take. Not until the young man leaves the spinning drunkards in the bar and walks out into the cold night does the first cut take place. And when it does, the effect is at once jarring and, retrospectively, beguiling. From that moment I abandoned all cynicism and committed myself to paying closer attention. It turned out that the entire film, which clocks in around 145 minutes, is composed from a series of only 39 shots. As I watched, I practically gawked at the boldness of relying on so many long, languid takes.

And the takes were, indeed, languid. Not a lot seems to happen for most of the film. Many of the shots simply follow János as he walks around a small Hungarian town at night. The whole thing unfolds at a truly glacial pace. But somehow those long takes feel completely riveting. They induce a special kind of tension and a heightened attentiveness. One grows to anticipate the next cut more than anything else. Consequently, the experience of watching the film becomes more about the continuities (and discontinuities) of the visual experience than about whatever’s going on in the plot. The film comes to seem strangely empty at times, and yet at the same time strangely full. Tarr’s cinematic precision conjures a sense of density and completeness, even when very little appears to be happening.

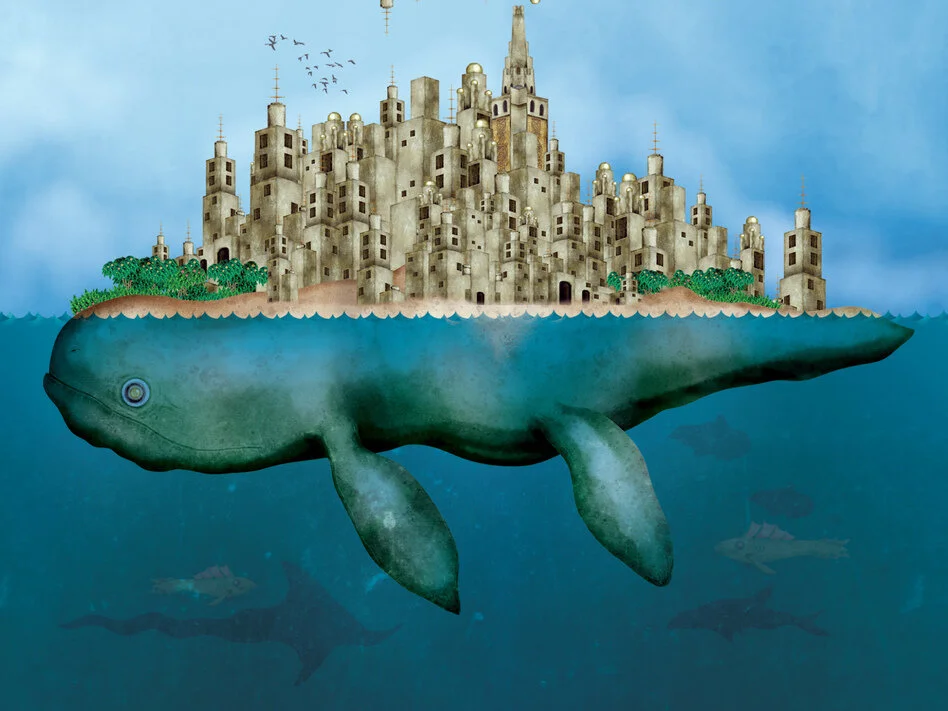

Which isn’t to imply that the film is plotless. Though I needn’t rehearse it here, there is certainly a story in Werckmeister Harmonies. And in fact, the story’s most profound moments possess even greater significance when they emerge from the slow morass of Tarr’s cinematic time. When János eventually makes his way to the center of town, where an ominous “circus” has arrived, he pays to enter the circus truck and encounters there a massive, stuffed whale with wide-open eyes. The strangeness of this dead whale is almost indescribable given the oppressive desolation of the surrounding village, and the riot that ensues later has an uncanny significance given the figurative distance between the circus’s disturbing spectacle and the town’s murky banality.

Aside from the haunting image of the dead whale’s massive open eye, what remained with me most from Werckmeister Harmonies was its visual density – the way Tarr constructs a compelling visual world through a series of 39 long shots that, as I indicated above, are at once empty and full. Also intriguing to me was how, by the end of these 39 shots, the Hungarian village at the center of the story had spun out of control and reached the brink of annihilation. Although I wouldn’t have put it in these words back then, something about Tarr’s slow-build apocalyptic vision fascinated me. And at the time I certainly didn’t have the intellectual wherewithal to pursue it further. In fact, I remember having such a strong reaction to Werckmeister Harmonies that I didn’t want to rush tracking down Tarr’s other films. The work was too good, too rich, to consume all at once. So I left it at that.

∞ ∞ ∞

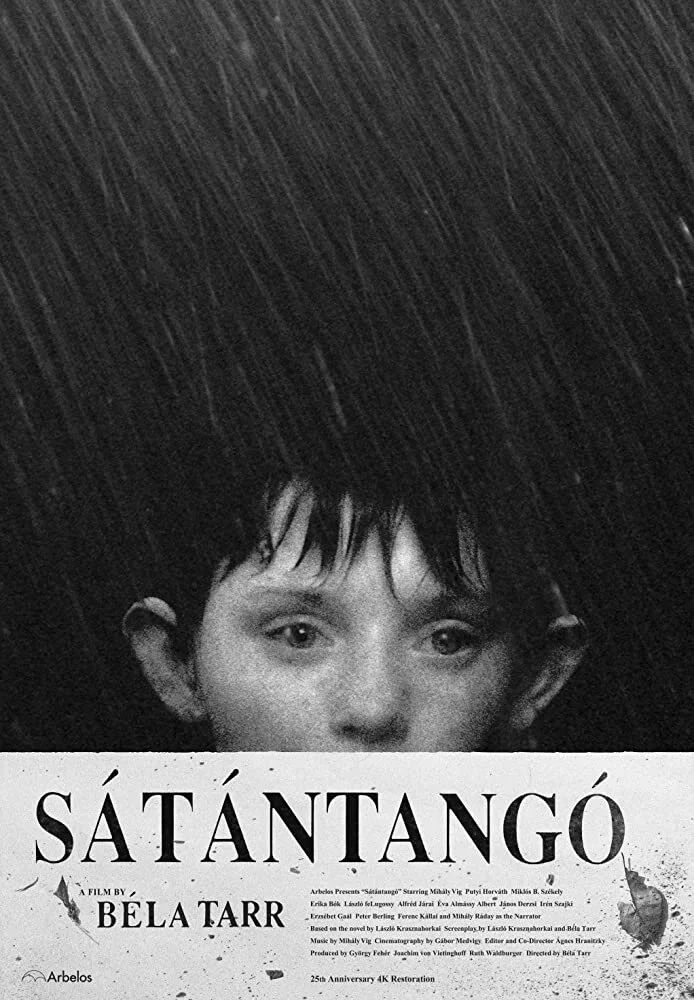

It wasn’t until some years later, when browsing the film collection at a local library, I stumbled upon another Tarr feature: his 432-minute epic from 1994, Satantango. I took the discovery as a sign and brought the DVD home. This time Tarr’s vision turned out to be too rich for me; I only ever got through the first seven minutes of the film, which also happens to be the length of the opening shot. To be sure, the shot is absolutely brilliant. The camera’s disembodied eye floats slowly through a muddy field and amongst a series of ramshackle buildings, all the while following a herd of cows moving from the barn to the field. The effect is far more magical than what any basic description can suggest. Somehow Tarr captured a veritable bovine ballet with subtle yet bewilderingly precise choreography. The camera moves slowly, but with surety, and as it glides along, cows move into and out of the distance, walking straight toward the camera at one point, and at other points inserting their heads into the picture just long enough to moo and retract. How did Tarr manage this?

However he did it, the cinematography, enigmatic and quiet, introduced a temporal paradox that I hadn’t experienced in film outside of Werckmeister Harmonies. Satantango’s geologically slow opening shot conjures a vast spaciousness, but it’s a spaciousness that nevertheless feels dense, a thickening of being. Swimming in the viscosity of Tarr’s cinematic time, seven minutes can seem a riveting eternity. Which explains why, when the camera finally cut away from the cows, I switched the movie off. I had to let Tarr’s opening gesture sink in. Regrettably, I never found the wherewithal to watch the remaining 422 minutes before I had to return it to the library. Shortly thereafter I moved away from the amazing library that provided access to the film, and the DVD has long been out of print. Satantango dropped out and away from consciousness.

(Incidentally, I found a copy at a movie rental store that specialized in hard-to-find films, but the 5-day rental requires a hefty deposit of $250! I also recently learned that a full restoration and rerelease of Satantango is on the horizon for 2019, which means the film will soon be much more accessible.)

Flash forward again, this time to my second year of grad school. I was perusing the New Fiction section in the university bookstore, when a strikingly designed hardcover volume caught my eye: all black, no dust jacket, and with strangely angled white lines striking through letters and across the cover’s empty spaces, creating an abstracted string figure. Written by some guy named László with a nigh-on-unpronounceable surname, the book was titled — you guessed it — Satantango.

It was only in this moment, after processing the cover’s strange verbal and visual language, that I made the connection: Tarr’s film of the same name had been based on a book — this book. And upon further investigation I discovered that Krasznahorkai had in fact been Tarr’s longtime collaborator. Their first film work together was Damnation (1988), for which Krasznahorkai wrote the screenplay, and their last collaboration was my beloved Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), which was based on Krasznahorkai’s second novel, translated into English as The Melancholy of Resistance. The premiere of Satantango precisely marked the halfway point in their period of working together.

This revelation of these artists’ collaboration thrilled me, and the idea that Tarr’s dense visuality may have been influenced by a literary vision piqued my interest. However, at the time of this discovery I was smack dab in the middle of a PhD program, which meant that pursuing this line of investigation would have to wait. And so my timeline flashes forward yet again, this time to early 2018, when, finally possessing the requisite time, energy, and interest, I resolved to read Satantango. What I found was, from the very first page, an exceedingly strange and entrancing work of fiction.

You will have noticed from the cover image of Satantango reproduced above that across the bottom there reads a quote from Susan Sontag declaring Krasznahorkai to be the “contemporary master of the Apocalypse.” This is no doubt the most famous of the blurbs to grace Krasznahorkai’s covers, and reading mainstream reviews of his work in translation clearly indicates the extent to which Sontag’s endorsement has influenced his English-language reception. This reception has grown rapidly in recent years — “rapidly” by the standards of the world of literary fiction in translation, anyway— following on the publication of Ottilie Mulzet’s translation of Seiobo There Below (2013) and John Batki, Ottilie Mulzet, and George Szirtes’ translation of The World Goes On (2017). These works have garnered significant international attention, particularly after Seiobo Down Below won both the Best Translated Book Award in 2014 and the Man Booker International Prize in 2015. Yet despite the mounting critical acclaim from influential critics like James Wood, and despite the accumulation of endorsements from literary heavyweights W. G. Sebald, Nicole Krauss, and Imre Kertész, one still finds Sontag’s blurb placed most prominently on Krasznahorkai’s covers, sometimes revised to read, “The Hungarian master of the Apocalypse.”

Why is Sontag’s declaration so ubiquitous? For one thing, it’s a great marketing strategy. Not only does the repetition function to brand Krasznahorkai, but it also capitalizes on his Eastern European mystique. (I’m thinking here of the quasi-medieval exoticism that often accompanies the appreciation of sacred-music composers like Arvo Pärt from Estonia and Giya Kancheli from Georgia.) For another thing, Sontag’s words are enticingly enigmatic. They don’t appear to come from a published review, so we have no way of divining what, exactly, she meant by them. This is cool insofar as her words retain a certain interpretive openness. So even though they could be seen to trade on the contemporary obsession with apocalyptic themes, one is also prepared not to find the usual trappings of apocalyptic fiction. And indeed, there are no zombies, plagues, or nuclear catastrophes to be found in Krasznahorkai’s books. What’s powerful about Sontag’s blurb, then, is the way it signals a unique treatment of the apocalypse theme that is not, in itself, overtly apocalyptic. In Krasznahorkai’s hands, apocalypse becomes a world-ending of another sort altogether.

But I’m afraid that before I go any further, a bit of a digression is in order. Stay with me, friends!

∞ ∞ ∞

Understanding Krasznahorkai’s unique brand of apocalypticism requires us first to understand something about how literary worldbuilding works. I’m not referring here to the particular techniques of literary worldbuilding, such as how to fabricate (fabulate?) a fictional world with a coherent and consistent logic and a built-in sense of cause and effect. I’m referring instead to a more general sense of what a literary world is in the first place.

Jeff VanderMeer offers a useful and nontechnical definition of literary worlds and worldbuilding in his gorgeously illustrated guide to creating imaginative fiction, Wonderbook. At the head of a chapter devoted to the subject he writes:

All fiction writers engage in some form of worldbuilding whether they call it that or call it the creation of “setting” or “milieu.” Even in the most extreme experimental cases, the writer can be said to have taken a position. Plonking down a tree in a desert along with two guys waiting for a third who never arrives still constitutes a setting. A “world” can be as small as a storage closet and as large as an entire universe; indeed, some stories have taken place on the underside of a leaf, within a single droplet of water. (211)

According to this understanding of world, every work of fiction establishes some kind of world. This goes as much for fictional depictions of the “real” world as it does for titanic feats of fantastical universe fabrication (see, most obviously, Tolkein’s Middle Earth). VanderMeer writes: “even ‘realistic’ fiction is not really all that realistic. . . . Instead, realistic fiction favors one particular stance or position over another and then builds a construct to support the stance. The approaches taken by some writers of nonrealistic fiction just tend to be more noticeable — the irony being that many fantasy writers use realistic techniques to achieve their effects” (211).

Those who seek a fuller exploration of this topic should consult Eric Hayot’s marvelous book, On Literary Worlds, a slim but mighty volume in which the author develops a conceptual vocabulary for understanding numerous aspects of fictional worlds, as well as fictional worlds’ relation to the world. For my purposes here, however, I want to stick with VanderMeer’s more basic definition of literary worldbuilding. In fact, I’d like to take his definition, which he wrote from the writer’s perspective, and turn it on its head, in order to reveal something about how literary worldbuilding works from the reader’s perspective.

Cover detail from Jeff VanderMeer’s Wonderbook. Image sourced from NPR.

For the reader, a novel could be said to begin in darkness. Or maybe not darkness, but a semi-luminescent twilight. After all, it is impossible to open a book (physical or electronic) without having some knowledge or assumptions about what one is getting into. This is due to the existence of what narratologist Gérard Genette called the “paratext” — that is, all the extratextual material that frames and “packages” any given text. The paratext includes such elements as the book’s cover, the author’s name, the publisher’s blurb, epigraphs, the preface, the dedication, chapter titles, the elements of design (e.g., typography, illustrations, font, etc.), and so on. The point here is that a reader can’t have a “pure” relationship to a text without the paratext somehow framing the experience.

So yes. Let’s say that for the reader, a novel begins not in perfect darkness, but in a kind of twilight. I’m going to call this twilight the Void. The reader occupies this semi-luminescent Void as she cracks the book open, leafs through the pages containing the book’s front matter, and arrives at the first page of text. Below the chapter headline, the reader begins reading. And as the reader reads, a world unfolds. Imagine that every word the reader reads introduces something new to the almost entirely blank Void she occupied just a moment before entering the text. With each word, she can “watch” in her mind’s eye as a new world manifests itself in real time.

I want to belabor this point just a while longer, in large part because I think the initial moments of worldbuilding are all to easily skipped over. I suspect that few readers consciously take a moment before plunging into a text to clear their mind and allow themselves to remain suspended at the threshold of the Void. But I would contend that it is the very existence of such a thing as this threshold Void moment that makes it so pleasurable to start a new book. Even if readers don’t notice it, it’s there. If it weren’t there, what else would explain why the first lines of novels feel so captivating? First words commence the unfolding of the world, and there is near infinite possibility for variation. Compare, for instance, just a couple of famous first lines. (I take these lines from a nearby mug, made by the Unemployed Philosopher’s Guild.)

Call me Ishmael. (Moby-Dick)

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. (Pride and Prejudice)

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. (1984)

A screaming came across the sky. (Gravity’s Rainbow)

What kinds of worlds do these sentences create? This is a good question to ask after reading any book’s first line, because at that point, from the reader’s perspective on the textual phenomenon, that line encapsulates the book’s entire world. In many ways, these first sentences, and the worlds they manifest, couldn’t be more different.

To begin, consider the effect of being directly addressed — commanded, even — by Herman Melville’s narrator. When the narrator of Moby-Dick says, “Call me Ishmael,” only two entities could be said to emerge from the Void: a speaker (this “Ishmael” fellow) and an addressee (the implied “you” of Ishmael’s command, the reader). Some kind of transactional space is also implied, though the spatial relationship is not yet clear. Are we meant to imagine being in a room together? Or is Ishmael only communicating via the text that we’re reading? This is a small world, to be sure, but a world nonetheless. And it’s a world that begs more questions than Moby-Dick, despite its capacious size, can answer. Who is this “Ishmael,” really? Is Ishmael his actual name, or will we only ever know him by an alias? How can we trust someone whose opening gambit is a command without an explanation? And furthermore, to what extent is Ishmael in narrative control? Is he responsible for the infamous chapters on cetology? And if so, is he also responsible for the chapters featuring Ahab alone in his cabin? Are these merely specimens of fabulation on Ishmael’s part? Nothing is certain.

Compare Melville’s confined and mysterious world with the logic of Jane Austen’s world, which begins with that supremely, coolly neutral word, “It.” In the sentence’s opening clause, the proposed universality of this “It” offers a broad yet completely abstract brushstroke. The clause makes a grandiloquent space-clearing gesture that in itself paradoxically fills space, injecting into the Void not an object but an attitude — and an attitude, I hasten to add, that is shared by a faintly implied body of individuals or institutions (i.e., those who universally acknowledge this truth). The next clause of the sentence introduces two concrete entities (a “single man” and a “good fortune”) into the world, and thus begins to clarify the nature of the universally acknowledged truth alleged in the first clause. The final clause ushers in a third object, the “wife” of which our “single man” must be “in want.” The introduction of the necessary wife clinches the logic of both the sentence and the world the sentence builds. Whereas Melville’s opening line sustains a mystery, Austen’s prefers analytical closure.

Examining Austen’s opening sentence alongside that of George Orwell is instructive in a different way; the comparison offers insight into more subtle variations in how first lines build worlds. Like Austen, Orwell begins with “It.” But his “It” isn’t the same as Austen’s “It.” His “It” proves less loaded, less universally generalizable. Nor it make a grand space-clearing gesture. Instead, Orwell’s “It” creates just enough space for a small bit of information: that we are talking about “a bright cold day in April.” So far, this world seems entirely normal and straightforward, as against Austen’s grandiosity. The normalcy seems to continue in the second half of the sentence, where a clock is striking the hour. But when the line’s final word hits, like the hammer hits the bell, the reader suddenly knows she is not in the “real” world. As with Austen, the power of Orwell’s opening sentence falls on the last word. But the effects these words have on the world being built are entirely different. Whereas Austen’s “wife” creates a closure that ensures logical consistency, Orwell’s “thirteen” blasts apart the presumed consistency of his apparently normal world and ushers us into a world that proves troublingly inconsistent.

The final sentence I’ve listed above, from Thomas Pynchon, is entirely unlike all of the others. Not only does it contain no people, it barely contains any objects: just a disembodied “screaming” that “came” (coming from where? going where?) across the sky. We certainly have three-dimensional space. The “sky” establishes a vertical axis, the word “across” establishes a horizontal axis, and the “screaming” echoes out in all directions. But beyond that, we remain completely unsure of what kind of context we’re in. Is this human screaming? Is it the screech of a missile? Are we in a suburb? A war zone? The questions proliferate.

I could go on and on (and on) with this kind of analysis. The main point of my indulging in all this worldbuilding talk has only been to suggest the vast variability in how opening lines instantiate worlds from out of what I’ve called the Void. And of course, each new word, sentence, paragraph, and so on continues the work of worldbuilding, right up to the very end. First lines are so potent because they initiate the unfolding, and so the worldbuilding work they do proves especially interesting. But the kind of analysis I’ve offered above applies just as much to the rest of the text — it’s just that the worldbuilding impact lessens with the introduction of each new “thing.” In many cases the reader feels reasonably immersed in a fictional world within a few pages, at which point the work of worldbuilding appears to halt. Effectively, though, that work never ends; it only becomes less obvious.

Which brings me to my last major point about literary worlds. The way in which literary worlds are constantly in the process of being built — that is, constantly being supplemented by the addition of words to an already long verbal string — reveals something about how such worlds are intrinsically fragile. No matter how many words an author links in a string, a text always maintains its relation to the Void from which it springs. And in fact, the more one pays attention to what has only been suggested and hence must be filled in by the reader’s imagination, the more one realizes how little it actually takes to manifest a world. And, by turn, how gossamer such a world can, in fact, be. The image of black text against the white background of the page provides a visual referent for this ongoing relation between literature and the Void. Shifting one’s focus from the words to the space that surrounds them offers the reader a reminder of the fundamental ephemerality of the literary text. The world, it suggests, is far emptier than full.

∞ ∞ ∞

Much of what I’ve written above needs to be worked out at greater length and with more rigor. But for now I want to return to my main point. All of this has been a necessary prelude to what I want to say about Krasznahorkai, so allow me, at last, to return to him. More specifically, allow me to turn to his second novel, Satantango.

Simply from a visual perspective, anyone who has read Krasznahorkai before would immediately find Satantango’s dense blocks of text familiar. Krasznahorkai tends not to break his writing into paragraphs. Full stops, too, can be few and far between, such that the reader may feel she is floundering in a ceaseless flow of language. Prominent literary critic James Wood notes the fluid nature of Krasznahorkai’s prose in a review essay titled “Madness and Civilization.” There he quotes Krasznahorkai’s foremost translator, George Szirtes, who refers to the author’s prose as “a slow lava-flow of narrative, a vast black river of type.” I find Szirtes’ description striking, for it nicely captures the density — the viscosity — of Krasznahorkai’s writing.

But I also think there’s more to be said about the effect such density/viscosity has on the reader. For one thing, when opening a Krasznahorkai book one cannot help but feel a sense of solidity and fullness. As I’ve already suggested, visually, it’s hard not to see the page as an image before one sees text; that is, the dense blocks of black print against the white page strike the eye before the reader registers individual words. The reader therefore encounters the surface of Krasznahorkai’s text like one encounters a physical wall. This sense of a thick materiality continues as the reader begins to read. Entering the world of the text feels like slowly sinking through some muddy passageway. The viscosity drags the reader down, like quicksand. If this comparison to quicksand seems like a leap, allow me to quote Satantango’s opening sentence, which in fact introduces the novel’s key thematic of mud and merciless murkiness:

One morning near the end of October not long before the first drops of the mercilessly long autumn rains began to fall on the cracked and saline soil on the western side of the estate (later the stinking yellow sea of mud would render footpaths impassable and put the town too beyond reach) Futaki woke to hear bells. (3)

Were I to perform the same exercise here that I did with the first sentences earlier, I’d start by pointing out how this one begins in a way not unlike the first sentence of 1984. Both sentences open by establishing a time and place that appear normal and consistent with the “real” world. Whereas the first sentence of 1984 maintains this pretense of normalcy until the final word, which swerves suddenly into the irreal when the clock strikes thirteen, the first sentence of Satantango makes a gradual descent into murkiness. After establishing time and place, the narrator turns to the future, anticipating “the first drops of the mercilessly long autumn rains” and “the stinking yellow sea of mud” that would eventually arrive. Yet this anticipated future can only be anticipated due to the fact that it repeats as part of an ongoing cycle, meaning that futurity here is a function of the past. The sentence concludes, following the parenthetical, with a return to the narrative present, as “Futaki woke to hear bells.”

Satantango therefore opens with a sentence that weaves past, present, and future into a continuity, and this thematic of continuity — along with the text’s visual density and linguistic viscosity — creates the effect of a seamless literary world. In short, Satantango’s mise-en-scène seems complete, an instant totality.

As one reads on, the seeming seamlessness of the novel’s literary world only grows more fully apparent, as Krasznahorkai continues to fashion his densely physical yet murky, rain-soaked world. However, although the sense of dreariness is firmly in place from the get go, the narrator in fact offers very few descriptive details about the setting. Specifics about the character Futaki and the house he is in appear very slowly, strung out across many sentences. As soon as Futaki enters the picture, Krasznahorkai’s worldbuilding becomes increasingly preoccupied with his perspective. He gazes blankly out a window and has an intense, drawn-out internal experience. It isn’t until we’re in the middle of a long sentence three pages into the novel that Futaki suddenly stirs from the window and “[turns] away from the sour smell of the perspiring Mrs. Schmidt.”

Who the hell is Mrs. Schmidt? Having been fully drawn into the dreariness of the world outside the house and the intensity inside Futaki’s mind, the sudden appearance of a second individual comes as something of a shock to the reader, and especially to the reader attuned to Krasznahorkai’s patient worldbuilding method. For what Mrs. Schmidt’s sudden irruption into the text indicates is that, against the apparent seamlessness of the fictional world, there had been a significant blind spot. Mrs. Schmidt not only punctures the seeming wholeness of the literary world; her appearance also creates suspicion that the kind of blindness that kept her invisible from the reader may in fact permeate the reader’s vision of the literary world. What had seemed whole instantly becomes full of holes — a perforated world constituted by an intrinsic dialectic of blindness and sight.

To be sure, and as I signaled earlier, the kind of dialectic I’ve just invoked between blindness and sight (or between holes and the whole) happens in all literary texts. Hell, it’s even an intrinsic aspect of all forms of perception. And although literary theorists like Paul de Man and Wolfgang Iser have written brilliantly on these and adjacent subjects, I have no desire here to regurgitate or rehearse their theories. Instead, I simply want to highlight two reasons why Satantango offers a significant test case. First, the novel’s form amplifies the blindness/sight (or hole/whole) dialectic intrinsic to literary worlding — which is to say, the density of the text as image and the viscosity of the prose work together to manifest an apparent wholeness that gets perforated in moments like Mrs. Schmidt’s irruption into the narration. Second, this dialectic plays a significant thematic role in the novel, which constantly foregrounds the trope of decay. Rain falls ceaselessly on the decrepit Hungarian village where the novel is set, and as a sergeant declares in chapter 2, “Everything is rotting in this place” (31). The novel is full of these types of declarations. And over time it comes to feel like, even as the novel unfolds and manifests its dense literary world, that same world is constantly melting back into primordial ooze. Often these contrary movements of the world’s manifestation and its melting feature in the same sentence, as in this long one from the novel’s first chapter:

Green mildew covered the cracked and peeling walls, but the clothes in the cupboard, a cupboard that was regularly cleaned, were also mildewed, as were the towels and all the bedding, and a couple of weeks was all it took for the cutlery saved in the drawer for special occasions to develop a coating of rust, and what with the legs of the big lace-covered table having worked loose, the curtains having yellowed and the lightbulb having gone out, they decided one day to move into the kitchen and stay there, and since there was nothing they could do to stop it happening anyway, they left the room to be colonized by the spiders and mice. (7)

Whether indoors or outdoors, everything in Satantango is on its way back to a state of nature.

And here, friends, I finally arrive at my point. What makes Satantango so remarkable is the way in which the literary worldbuilding is so tightly interwoven with the apocalyptic such that, at any given moment, the novel’s fictional world is being created and destroyed. To continue with the weaving metaphor, if the text’s weft is constituted by the emergence of a world, it’s warp is constituted by that same world’s degeneration into the primordial. Even on a sentence level there plays out the rhythmic passage out of and back into the Void.

What Satantango has helped me to see is how literary worlds come into being in the midst of their own dissolution. Krasznahorkai may foreground this weird, Vishnu-like nature of the creation and destruction of literary worlds through the viscous apocalypticism of this particular novel. And yet I have a hunch that there always exists this kind of relationship between literature and the Void. I also suspect that further lessons may be drawn from this relationship. As this essay represents but the first, tentative steps into this new research, unspooling these further lessons will have to wait for another day.

László Krasznahorkai. Image sourced from The New Yorker.

Works Cited

De Man, Paul. Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism. U of Minnesota P, 1983.

Hayot, Eric. On Literary Worlds. Oxford UP, 2012.

Iser, Wolfgang. The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Johns Hopkins UP, 1980.

Krasznahorkai, László. Melancholy of Resistance. Translated by George Szirtes. New Directions, 2002.

———. Satantango. Translated by George Szirtes. New Directions, 2012,

———. Seiobo There Below. Translated by Ottilie Mulzet. New Directions, 2013.

———. The World Goes On. Translated by John Batki, Ottilie Mulzet, and George Szirtes. New Directions, 2017.

Merhige, E. Elias. Begotten. DVD. World Artists, 2001.

Tarr, Béla. Damnation. DVD. Facets Video, 2006.

———. Sátántangó. DVD. Facets Video, 2008.

———. Werckmeister Harmonies. DVD. Facets Video, 2006.

VanderMeer, Jeff. Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction. Abrams Image, 2013.

Wood, James. “Madness and Civilization.” The New Yorker, 4 July 2011. Available here.